Lightning protection, static control in oil and gas installations

Exposure from lightning strikes and buildup of static electricity within the oil and gas industry has been around for years and continues to be a major source of oil field equipment losses across the United States. With the ongoing threat of inclement weather and moderate number of lightning strikes associated with storms, protection of equipment susceptible to lightning damage is at the forefront in risk mitigation. Here at Hanover we offer technical solutions aimed at maintaining less downtime and equipment losses associated with lightning strikes.

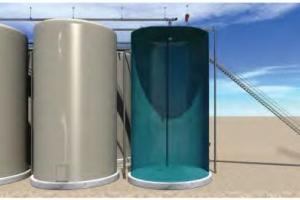

A common equipment related threat stems from aboveground tanks containing oilfield fluids. Hydrocarbon mixtures become volatile when the air to fuel ratio reaches ignition range and is presented with an ignition source. Listed below are common concerns and possible remedies with the above-mentioned.

Lightning strikes-direct/indirect

Not all lightning strikes require direct contact to damage exposed oilfield equipment. A nearby lightning strike can create a chain reaction promoting fire/explosion to an entire site’s tanks, fluids and equipment. Although both are effective, two types of lightning protection are typically installed at well sites and well servicing operations — a “catenary” method and a “static dissipation” process.

The preferred method is dissipation involving use of small wire brush apparatuses formed in the shape of spheres. Static electricity tends to flow more efficiently from sharp pointed edges as compared to flat wide surfaces. Static electricity suspended in the surrounding atmosphere is dissipated back into a ground system and creates a less attractive area for lightning to strike.

Catenary lightning protection utilizes a pole grid system allowing lightning to strike a lightning rod mounted on a tall pole structure and directs the lightning strike and associate electric current to a grounded system.

Bonding/grounding

Equipment, especially aboveground fluid storage tanks, require a bonding/grounding method that ensures static electricity flows to the earth through a grounded system. Conductive materials that makeup construction of oilfield equipment, for example thief hatches or metal valves, should be bonded to a grounded system to maximize continuous electrical connectivity to ground. Properly bonded and grounded equipment controls electrical arcing, thus reducing the introduction of an ignition source within a potentially volatile vapor space associated with tanks containing oilfield fluids.

Static concerns

Fluid movement and load out stations: Movement of fluids within tanks can create a static charge, which typically dissipates within conductive walls of a steel tank. However, fiberglass tanks typically contain a static charge allowing for a possible arcing process that provides an ignition source within potentially volatile atmospheres. Internal static dissipation applications connected to an outside grounded source provide a means to control arcing within the interior of a tank.

Oilfield workers can carry static charges within a high static environment. Typically, the first conductive object touched transfers the charge. For example, touching a thief hatch on a tank containing volatile fluids could introduce an ignition source. Bonding conductive materials to a secured grounding system is a best practice to control electric arcing.

Truck load out lines can also contain static charges and should be bonded to a secure grounded source to ensure electrical charges are dissipated into the earth.

For more information contact your Hanover Risk Solutions consultant.

LC 2017-378

This material is provided for informational purposes only and does not provide any coverage or guarantee loss prevention. The examples in this material are provided as hypothetical and for illustration purposes only. The Hanover Insurance Company and its affiliates and subsidiaries (“The Hanover”) specifically disclaim any warranty or representation that acceptance of any recommendations contained herein will make any premises, or operation safe or in compliance with any law or regulation. By providing this information to you, The Hanover does not assume (and specifically disclaims) any duty, undertaking or responsibility to you. The decision to accept or implement any recommendation(s) or advice contained in this material must be made by you.

Lightning protection, static control in oil and gas installations

Exposure from lightning strikes and buildup of static electricity within the oil and gas industry has been around for years and continues to be a major source of oil field equipment losses across the United States. With the ongoing threat of inclement weather and moderate number of lightning strikes associated with storms, protection of equipment susceptible to lightning damage is at the forefront in risk mitigation. Here at Hanover we offer technical solutions aimed at maintaining less downtime and equipment losses associated with lightning strikes.

A common equipment related threat stems from aboveground tanks containing oilfield fluids. Hydrocarbon mixtures become volatile when the air to fuel ratio reaches ignition range and is presented with an ignition source. Listed below are common concerns and possible remedies with the above-mentioned.

Lightning strikes-direct/indirect

Not all lightning strikes require direct contact to damage exposed oilfield equipment. A nearby lightning strike can create a chain reaction promoting fire/explosion to an entire site’s tanks, fluids and equipment. Although both are effective, two types of lightning protection are typically installed at well sites and well servicing operations — a “catenary” method and a “static dissipation” process.

The preferred method is dissipation involving use of small wire brush apparatuses formed in the shape of spheres. Static electricity tends to flow more efficiently from sharp pointed edges as compared to flat wide surfaces. Static electricity suspended in the surrounding atmosphere is dissipated back into a ground system and creates a less attractive area for lightning to strike.

Catenary lightning protection utilizes a pole grid system allowing lightning to strike a lightning rod mounted on a tall pole structure and directs the lightning strike and associate electric current to a grounded system.

Bonding/grounding

Equipment, especially aboveground fluid storage tanks, require a bonding/grounding method that ensures static electricity flows to the earth through a grounded system. Conductive materials that makeup construction of oilfield equipment, for example thief hatches or metal valves, should be bonded to a grounded system to maximize continuous electrical connectivity to ground. Properly bonded and grounded equipment controls electrical arcing, thus reducing the introduction of an ignition source within a potentially volatile vapor space associated with tanks containing oilfield fluids.

Static concerns

Fluid movement and load out stations: Movement of fluids within tanks can create a static charge, which typically dissipates within conductive walls of a steel tank. However, fiberglass tanks typically contain a static charge allowing for a possible arcing process that provides an ignition source within potentially volatile atmospheres. Internal static dissipation applications connected to an outside grounded source provide a means to control arcing within the interior of a tank.

Oilfield workers can carry static charges within a high static environment. Typically, the first conductive object touched transfers the charge. For example, touching a thief hatch on a tank containing volatile fluids could introduce an ignition source. Bonding conductive materials to a secured grounding system is a best practice to control electric arcing.

Truck load out lines can also contain static charges and should be bonded to a secure grounded source to ensure electrical charges are dissipated into the earth.

For more information contact your Hanover Risk Solutions consultant.

LC 2017-378

This material is provided for informational purposes only and does not provide any coverage or guarantee loss prevention. The examples in this material are provided as hypothetical and for illustration purposes only. The Hanover Insurance Company and its affiliates and subsidiaries (“The Hanover”) specifically disclaim any warranty or representation that acceptance of any recommendations contained herein will make any premises, or operation safe or in compliance with any law or regulation. By providing this information to you, The Hanover does not assume (and specifically disclaims) any duty, undertaking or responsibility to you. The decision to accept or implement any recommendation(s) or advice contained in this material must be made by you.

Lightning protection, static control in oil and gas installations

Exposure from lightning strikes and buildup of static electricity within the oil and gas industry has been around for years and continues to be a major source of oil field equipment losses across the United States. With the ongoing threat of inclement weather and moderate number of lightning strikes associated with storms, protection of equipment susceptible to lightning damage is at the forefront in risk mitigation. Here at Hanover we offer technical solutions aimed at maintaining less downtime and equipment losses associated with lightning strikes.

A common equipment related threat stems from aboveground tanks containing oilfield fluids. Hydrocarbon mixtures become volatile when the air to fuel ratio reaches ignition range and is presented with an ignition source. Listed below are common concerns and possible remedies with the above-mentioned.

Lightning strikes-direct/indirect

Not all lightning strikes require direct contact to damage exposed oilfield equipment. A nearby lightning strike can create a chain reaction promoting fire/explosion to an entire site’s tanks, fluids and equipment. Although both are effective, two types of lightning protection are typically installed at well sites and well servicing operations — a “catenary” method and a “static dissipation” process.

The preferred method is dissipation involving use of small wire brush apparatuses formed in the shape of spheres. Static electricity tends to flow more efficiently from sharp pointed edges as compared to flat wide surfaces. Static electricity suspended in the surrounding atmosphere is dissipated back into a ground system and creates a less attractive area for lightning to strike.

Catenary lightning protection utilizes a pole grid system allowing lightning to strike a lightning rod mounted on a tall pole structure and directs the lightning strike and associate electric current to a grounded system.

Bonding/grounding

Equipment, especially aboveground fluid storage tanks, require a bonding/grounding method that ensures static electricity flows to the earth through a grounded system. Conductive materials that makeup construction of oilfield equipment, for example thief hatches or metal valves, should be bonded to a grounded system to maximize continuous electrical connectivity to ground. Properly bonded and grounded equipment controls electrical arcing, thus reducing the introduction of an ignition source within a potentially volatile vapor space associated with tanks containing oilfield fluids.

Static concerns

Fluid movement and load out stations: Movement of fluids within tanks can create a static charge, which typically dissipates within conductive walls of a steel tank. However, fiberglass tanks typically contain a static charge allowing for a possible arcing process that provides an ignition source within potentially volatile atmospheres. Internal static dissipation applications connected to an outside grounded source provide a means to control arcing within the interior of a tank.

Oilfield workers can carry static charges within a high static environment. Typically, the first conductive object touched transfers the charge. For example, touching a thief hatch on a tank containing volatile fluids could introduce an ignition source. Bonding conductive materials to a secured grounding system is a best practice to control electric arcing.

Truck load out lines can also contain static charges and should be bonded to a secure grounded source to ensure electrical charges are dissipated into the earth.

For more information contact your Hanover Risk Solutions consultant.

LC 2017-378

This material is provided for informational purposes only and does not provide any coverage or guarantee loss prevention. The examples in this material are provided as hypothetical and for illustration purposes only. The Hanover Insurance Company and its affiliates and subsidiaries (“The Hanover”) specifically disclaim any warranty or representation that acceptance of any recommendations contained herein will make any premises, or operation safe or in compliance with any law or regulation. By providing this information to you, The Hanover does not assume (and specifically disclaims) any duty, undertaking or responsibility to you. The decision to accept or implement any recommendation(s) or advice contained in this material must be made by you.

Lightning protection, static control in oil and gas installations

Exposure from lightning strikes and buildup of static electricity within the oil and gas industry has been around for years and continues to be a major source of oil field equipment losses across the United States. With the ongoing threat of inclement weather and moderate number of lightning strikes associated with storms, protection of equipment susceptible to lightning damage is at the forefront in risk mitigation. Here at Hanover we offer technical solutions aimed at maintaining less downtime and equipment losses associated with lightning strikes.

A common equipment related threat stems from aboveground tanks containing oilfield fluids. Hydrocarbon mixtures become volatile when the air to fuel ratio reaches ignition range and is presented with an ignition source. Listed below are common concerns and possible remedies with the above-mentioned.

Lightning strikes-direct/indirect

Not all lightning strikes require direct contact to damage exposed oilfield equipment. A nearby lightning strike can create a chain reaction promoting fire/explosion to an entire site’s tanks, fluids and equipment. Although both are effective, two types of lightning protection are typically installed at well sites and well servicing operations — a “catenary” method and a “static dissipation” process.

The preferred method is dissipation involving use of small wire brush apparatuses formed in the shape of spheres. Static electricity tends to flow more efficiently from sharp pointed edges as compared to flat wide surfaces. Static electricity suspended in the surrounding atmosphere is dissipated back into a ground system and creates a less attractive area for lightning to strike.

Catenary lightning protection utilizes a pole grid system allowing lightning to strike a lightning rod mounted on a tall pole structure and directs the lightning strike and associate electric current to a grounded system.

Bonding/grounding

Equipment, especially aboveground fluid storage tanks, require a bonding/grounding method that ensures static electricity flows to the earth through a grounded system. Conductive materials that makeup construction of oilfield equipment, for example thief hatches or metal valves, should be bonded to a grounded system to maximize continuous electrical connectivity to ground. Properly bonded and grounded equipment controls electrical arcing, thus reducing the introduction of an ignition source within a potentially volatile vapor space associated with tanks containing oilfield fluids.

Static concerns

Fluid movement and load out stations: Movement of fluids within tanks can create a static charge, which typically dissipates within conductive walls of a steel tank. However, fiberglass tanks typically contain a static charge allowing for a possible arcing process that provides an ignition source within potentially volatile atmospheres. Internal static dissipation applications connected to an outside grounded source provide a means to control arcing within the interior of a tank.

Oilfield workers can carry static charges within a high static environment. Typically, the first conductive object touched transfers the charge. For example, touching a thief hatch on a tank containing volatile fluids could introduce an ignition source. Bonding conductive materials to a secured grounding system is a best practice to control electric arcing.

Truck load out lines can also contain static charges and should be bonded to a secure grounded source to ensure electrical charges are dissipated into the earth.

For more information contact your Hanover Risk Solutions consultant.

LC 2017-378

This material is provided for informational purposes only and does not provide any coverage or guarantee loss prevention. The examples in this material are provided as hypothetical and for illustration purposes only. The Hanover Insurance Company and its affiliates and subsidiaries (“The Hanover”) specifically disclaim any warranty or representation that acceptance of any recommendations contained herein will make any premises, or operation safe or in compliance with any law or regulation. By providing this information to you, The Hanover does not assume (and specifically disclaims) any duty, undertaking or responsibility to you. The decision to accept or implement any recommendation(s) or advice contained in this material must be made by you.